As protests against China’s «covid zero» policy swept the country over the weekend and this week, there is more to people protesting than meets the eye.

The most immediate trigger for this wave of protests was the deadly fire in Urumqi, which sparked public outrage that lockdown measures prevented emergency services from reaching the victims. However, a deeper cause of this unrest is that the protesters are responding to a broken social contract between the Chinese Communist Party and the people. This is a contract that guarantees people’s sustenance —basic food, housing, and security— in exchange for their consent to be judged.

As an expert on Chinese politics, he expected that prolonged lockdowns and economic downturns would trigger dissatisfaction and spontaneous protests. But he did not expect the wave of protests to break out in Many cities through mainland China, a rare occurrence. He also did not expect the protesters to be so rampant in their calls for freedom and democracyin addition to demanding an end to the confinements.

As the “zero covid” policy dragged on, it became clear that the Chinese government is no longer honoring its end of the bargain to ensure basic livelihoods.

Since the crushed pro-democracy movement in Tiananmen Square in 1989, the Chinese people have largely learned to stay out of politics. Young Chinese have undergone an intense patriotic education that teaches them to be loyal to the ruling Communist Party and to see democracy, freedom and human rights as dangerous «western» values. Until now, the most vociferous Chinese youth have been the ultranationalists.»little roses” who cyberbully their peers who are critical of the Chinese government.

However, this time young protesters both inside and outside China are the faces of a form of opposition mobilization, rather than nationalist.

How did this come about?

On the one hand, the protests were facilitated by the rapid spread on social media despite censorship. In the run-up to the 20th Party Congress in October, a lone dissident in Beijing deployed protest banners calling people to say no to censorship, yes to freedom; not to be slaves, but to be citizens. Despite swift censorship, a Chinese social media post referencing the incident had been viewed 180,000 times before being erased.

Chinese university students abroad too amplified the slogans of the lone dissident on bulletin boards and social media accounts. Although largely anonymous, they broke the silence and entered risky social movement territory. These trailblazers were harbingers of the defining moment inside China this past weekend.

But the bigger question is why the protests broke out at this time.

In part, this has to do with pent-up frustrations over the zero-Covid lockdowns that have affected his colleagues, friends, families, and his future. With the economic slowdown, an estimated 1 in 5 young people in China are unemployed. The protesters were also reacting to the injustice of multiple preventable human tragedies. It wasn’t just the Urumqi fire. A earthquake in september it drew criticism over lockdown measures when residents were prevented from fleeing the disaster, and the draconian restrictions of the pandemic have routinely prevented people from accessing life-saving services. medical treatment.

Chinese citizens had largely accepted the lack of political freedoms in exchange for basic guarantees of a safe and stable life, but now the latter has been severely compromised. In the early days of the pandemic, when the death toll rose astronomically in the United States and other Western democracies, many Chinese felt that their social contract, one that prioritizes survival over personal freedom, was superior. They could «eat bitterness» with quarantines, frequent controls of health codesand blockades as long as it guaranteed their survival.

But as the “zero covid” policy has dragged on, it has become clear that the Chinese government is no longer living up to its end of the bargain to ensure basic livelihoods. With 20% youth unemployment, business closingmigrant workers left Homeless Y preventable deaths increasing, some Chinese citizens are withdrawing their consent to be governed.

Remarkably, protesters inside and outside of China are demanding not only economic livelihood, but also political rights, including freedom of expression. Previously, Chinese dissidents and human rights activists were the ones to adopt that language. Chinese protesters typically avoid such rhetoric, preferring to stick to basic economic or local issues, which are more likely to draw concessions. They understand that talking about freedom is like playing with fire.

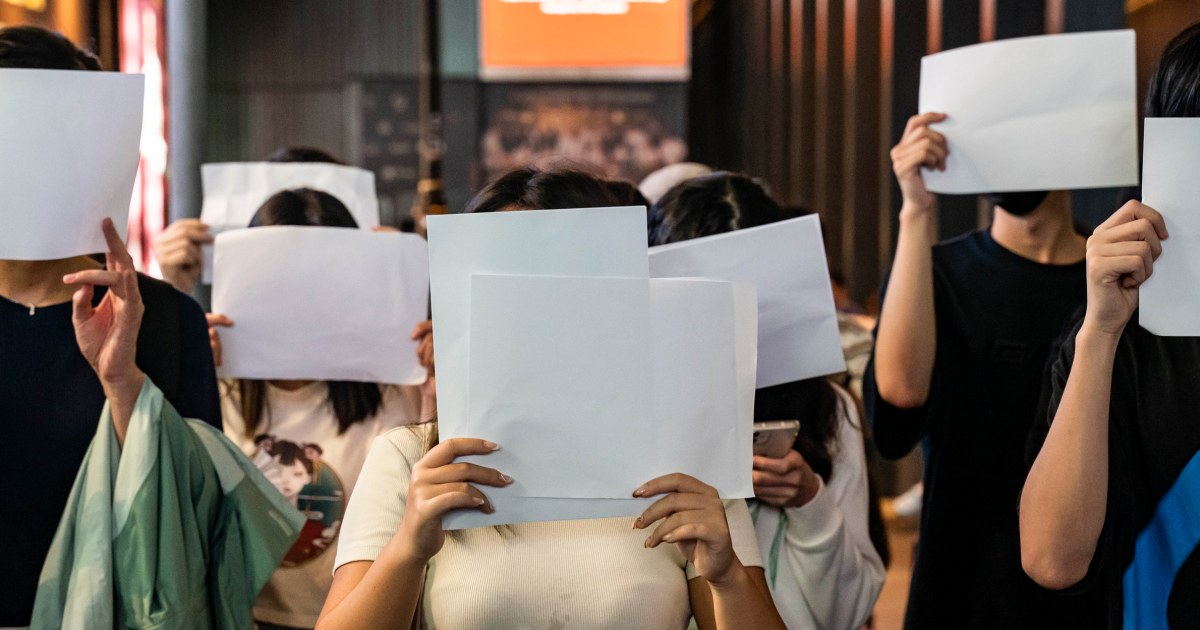

It is significant that this time, the Chinese protesters are loan a tactic of Hong Kong protesters in 2020: holding blank pieces of paper. This tactic visually exposes the absurd nature of censorship in China. So many words have been declared off-limits that citizens feel they can only express their discontent through a blank sheet of paper. This blank space represents all the words that you want to express but cannot. It suggests the beginnings of a political awakening in which people realize that mere survival is not enough; they must also be able to express themselves.

Despite the divisive nature of these protests, it is premature to call it a revolution. We do not yet know the full scale of such protests, nor do we know how long they will continue, given that China’s strong security apparatus is already in place. Not all of the country’s 1.4 billion people are in rebellion. In fact, the protesters may represent a small but vociferous segment of the citizenry.

However, these protests should not be judged based on whether they can change policy, although government concessions are already evident with the restrictions imposed. partially raised in certain locations. They must be seen for what they are: expressions of dissent by certain members of a society who have endured too much and been silenced for too long.