An international team of scientists from different disciplines has joined forces and, for the first time in history, has managed to ‘resurrect’ molecules up to 100,000 years old. As published by the authors of this achievement in an article by the ‘Science’ magazinethe union of knowledge archaeologists, bioinformaticians, molecular biologists, and chemists has made it possible to turn laboratories into true time machines, travel to the Ice Age and discover, for example, several extinct microorganism species which were unknown until now.

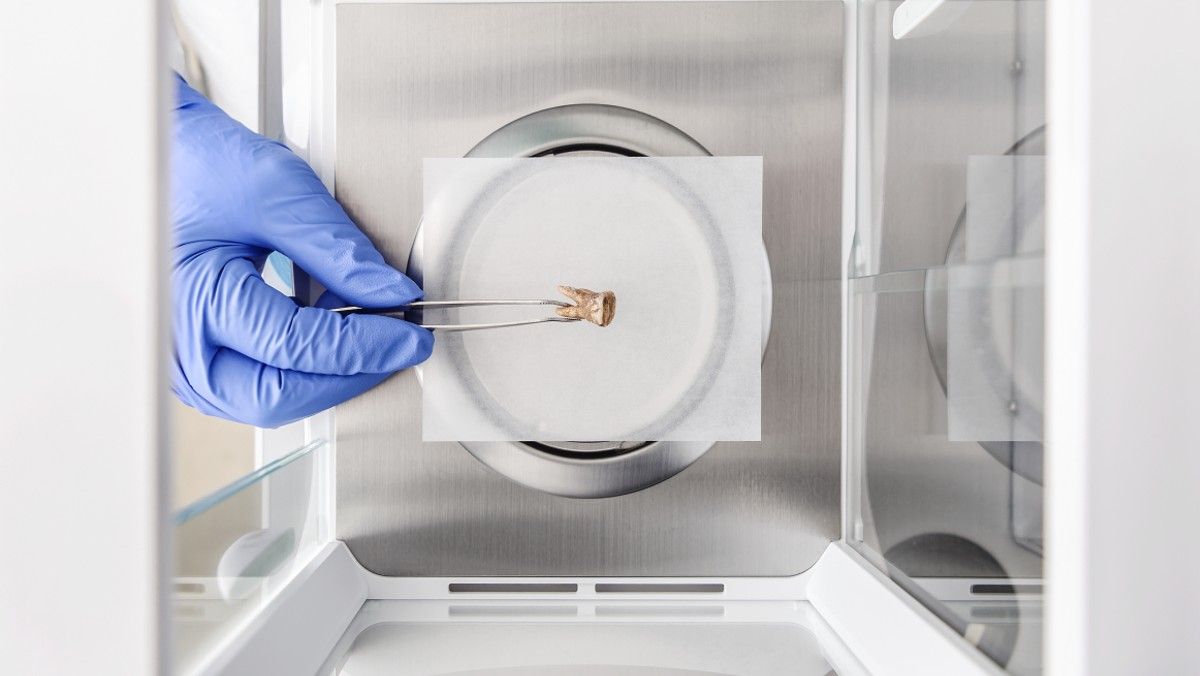

The investigation, published this Thursday, is based in dental remains of 12 Neanderthals They lived between 100,000 and 40,000 years ago. 34 modern humans between 30,000 and 150 years old and 18 contemporary humans. The scientists focused specifically on the tartar dental study: the only part of the body that routinely fossilizes during life and which, in turn, becomes a kind of graveyard for mineralized bacteria.

One of the dental samples that most surprised the experts was the one known as ‘Red lady from El Mirón’, an adult woman who lived 19,000 years ago in the rugged mountains of Cantabria. The study of her teeth allowed us to find the remains of a hitherto unknown oral bacterium of the genus ‘Chlorobium’. This same microbe was also found in other seven paleolithic humans and neanderthals.

How to resurrect a molecule

Once the remnants of these ancient bacteriascientists used synthetic molecular biotechnology tools to ‘resuscitate’. They started by taking actual live bacteria, introduced part of these ancient genes and, from there, they ‘reactivated’ them so that they would work again. This is the first time that this type of tool has been used in ancient bacteria. «This is the first step to access chemical diversity hidden from microbes from Earth’s past,» explains Martin Klapper, a researcher at the University of Leibniz-HKI and co-author of this study.

«This is the first step in accessing the hidden chemical diversity of microbes from Earth’s past»

Related news

According to the experts who have led this work, this new technique adds an exciting new dimension to the discovery of compounds from the past. «Now we can start working with billions of unknown ancient DNA fragments and order them systematically in missing bacterial genomes as far back as the Ice Age,» says Alexander Hübner, postdoctoral researcher at MPI-EVA and co-author of this paper.

This scientific milestone, led by experts from Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and the Harvard Universitycould open up a new area of study focused, for example, on studying the microbial and chemical genetic diversity of our past. «Our goal is to chart a path for the discovery of ancient compounds and inform about their possible future applications,» explains the team of experts who have achieved this milestone with enthusiasm.